Defining Minimalism: Purpose, Simplicity, and Real-Life Challenges

Blog Title: Defining Minimalism: Purpose, Simplicity, and Real-Life Challenges

In a world that celebrates abundance, could living with less actually lead to a richer life?

In my journey of embracing minimalism, I’ve explored its connection to wellbeing. Now, I’m delving into what truly defines this lifestyle.

What is Minimalism?

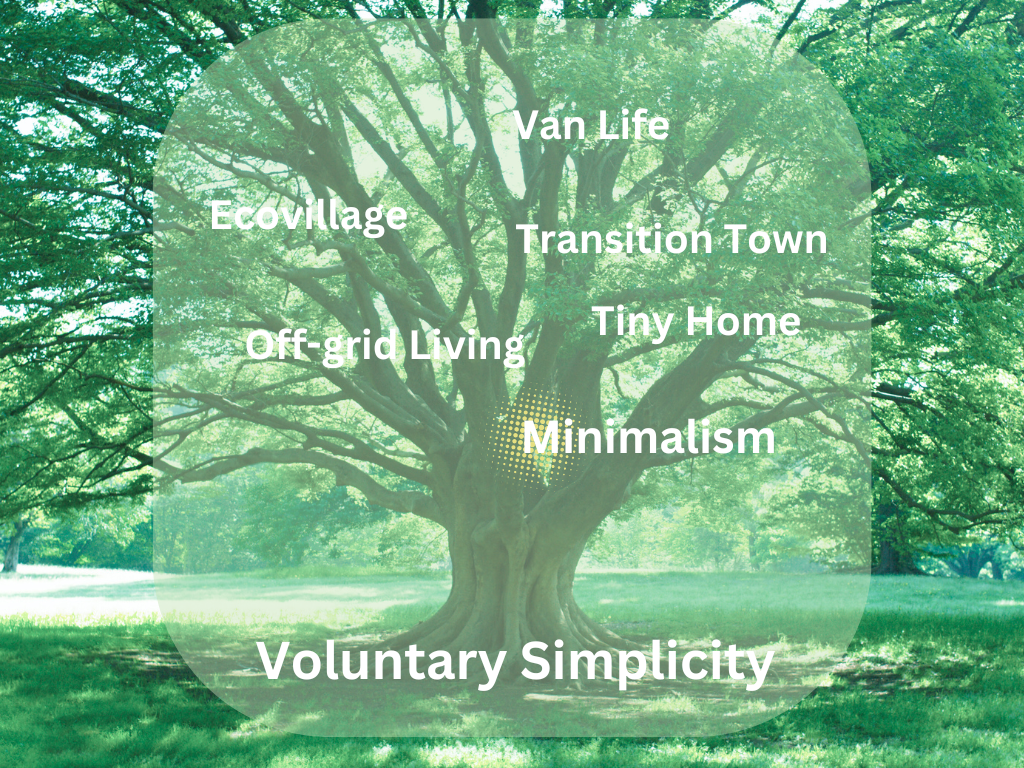

Imagine Voluntary Simplicity (VS) as a huge, rooted tree—its branches reaching deep into history, philosophy, and spiritual wisdom. Minimalism? Think of it as one of its sturdy branches, now sprouting its own fresh leaves, hashtags, and even Netflix specials. Urban minimalism is one of those fresh leaves, especially suited to today’s fast-paced city life.

The Roots of Voluntary Simplicity

The term "Voluntary Simplicity" was coined by Richard Gregg, a student of Gandhi, back in 1936. Gregg envisioned a lifestyle that limited possessions, avoided clutter, and aligned with personal purpose (Gregg, 1936). It wasn’t just about having less; it was about making space for what truly matters. This philosophy evolved into modern-day practices like tiny homes, off-grid living, ecovillages, van life, and minimalism—a lifestyle demonstrating how less can be more, and even better.

Voluntary Simplicity and Minimalism

From Gregg’s time to today, VS has drawn deep thinkers to its cause. Henry David Thoreau, for instance, spent two years living with bare necessities by Walden Pond, Massachusetts, and famously advised others to "simplify, simplify" (Thoreau, 1854). Even then, people struggled with "too much stuff."

VS has been described as "embracing frugality" with a strong sense of environmental urgency, as “returning to human-scale living,” and as a path toward "higher human potential." It calls us to use less, love more, and connect with nature and one another (Elgin & Mitchell, 1977).

Minimalism: The Urbanite's Take on Voluntary Simplicity

Minimalism, one particularly “on-trend” branch of VS, adapts these ideas to modern, urban life (Hausen, 2019). It emphasizes intentional simplicity, reducing possessions, and valuing experiences over consumerism. Urban minimalism has especially appealed to city-dwellers, with its vision of uncluttered living, less stress about “stuff,” and a shift toward life’s intangibles.

While minimalism definitions vary, minimalists usually ask, “What do I truly need to live well?” and let go of the rest.

Today, minimalism is part of a wider movement fueled by influencers, books, and documentaries, each showcasing how scaling back can lead to richer lives. Whether through YouTube channels like The Minimalists or Facebook groups like Minimalist Mom, today’s minimalists reveal that less can indeed be more.

Where Urban Minimalism Fits In

Urban minimalism is about harmonizing simple living principles with the fast pace of city life. Urban minimalists focus on quality experiences, meaningful connections, and community involvement while resisting the lure of excess consumption that city living often encourages.

Beyond a Passing Trend

Urban minimalism is rooted in a long-standing legacy, one shaped by figures like Lao-Tsu, Buddha, Jesus, and the Stoics, who taught that happiness often comes from contentment rather than accumulation. Today, minimalism has gained fresh momentum with the rise of environmentalism and anti-consumerism, helping people reconnect with their values in a world that continually pushes us to buy and consume more.

Urban minimalism encourages us to ask ourselves: What truly matters? How do I define “enough”? And perhaps most challenging of all, do I really need another pair of shoes?

Minimalism in Real Life

Minimalism is more than just “decluttering”; it’s a mindset rooted in intentionality and sustainability. According to Kang et al. (2021), some key elements of minimalism include:

Clutter Removal: Releasing what no longer serves us.

Mindful Shopping: Buying intentionally and purposefully.

Product Longevity: Choosing quality over quantity, so less ends up in landfills.

Self-Sufficiency: Learning to live without constantly needing more.

Minimalism offers an alternative to a high-consumption society, advocating for intentional and sustainable living. Researchers like Jain et al. (2023) describe minimalism as “deciding what matters most and having the courage to let go of the rest.” However, embracing this lifestyle raises some practical and ethical questions about its broader implications.

Critiques on Minimalism

Minimalism has been widely praised, yet some aspects warrant critical reflection. Here are a few concerns that challenge its idealism:

A Lifestyle for the Privileged? Minimalism can sometimes come across as accessible only to those who can afford to be selective and buy high-quality items and neglect the real problem of global inequalities (Meissner, 2019). Not everyone has the financial flexibility to invest in durable, often expensive products. Does this exclusivity contradict the inclusive, less-is-more philosophy?

Environmental Impact of Decluttering: Decluttering often focuses on keeping only what “sparks joy,” but this doesn’t account for the waste produced by discarding the rest that contributes to overflowing garbage dumps. How mindful are we about the environmental impact of where our decluttered items end up?

Minimalism as a Commodity: Ironically, minimalism has become something to consume—self-help books, documentaries, online blogs, social media posts, workshops, decluttering consulting services, and lifestyle brands all market a “minimalist” lifestyle. This paradox reveals the commercialization of minimalism, as products and services marketed as ‘minimalist’ may contribute to consumption habits that inadvertently support capitalist growth (Sandlin et al., 2022), raising questions about the sustainability of minimalistic practices within a consumer-driven society.

My Definition of Minimalism

For me, minimalism is an intentional lifestyle choice focusing on what truly matters. It reduces consumption and materialism while promoting environmental responsibility, social awareness, spirituality, and personal development.

A few phrases guide me: No-Buy, Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle. My journey toward minimalism has rewarded me in ways I never expected, including a boost to my savings, energy, and time, allowing me to focus on what matters most.

Minimalism invites us to take a hard look at our lives and re-evaluate what we truly need and value. But it also calls us to consider the impact of our choices—on ourselves, our communities, and our planet.

What About You?

Whether you’re considering minimalism or simply want to declutter your mind, urban minimalism invites you to embrace intentionality. It’s not about the quantity of possessions but about quality of life and planetary health—because, in the end, less can be more.

Minimalism doesn’t have to be rigid; it can adapt to your values and lifestyle.

Could minimalism offer not just a life with less but a life of more—more peace, more meaning, and more joy?

I welcome your thoughts and reflections on your experience with minimalism.

Take care until the next post!

References

Elgin, D., & Mitchell, A. (1977). Voluntary Simplicity. Duane Elgin on sustainability, consciousness, and our world in transition. https://duaneelgin.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/voluntary_simplicity.pdf

Gregg, R. B. (1936). The value of voluntary simplicity. https://duaneelgin.com/value-voluntary-simplicity/

Hausen, J. E. (2019). Minimalist life orientations as a dialogical tool for happiness. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 47(2), 168–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2018.1523364

Jain, V. K., Gupta, A., & Verma, H. (2023). Goodbye materialism: exploring antecedents of minimalism and its impact on millennials’ well-being. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03437-0

Kang, J., Martinez, C. M. J., & Johnson, C. (2021). Minimalism as a sustainable lifestyle: Its behavioral representations and contributions to emotional well-being. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 27, 802–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.02.001

Meissner, M. (2019) Against accumulation: lifestyle minimalism, de-growth and the present post-ecological condition. Journal of Cultural Economy, 12:3, 185-200, DOI: 10.1080/17530350.2019.1570962

Sandlin, J. A., Wallin, J., & James, J. (2022). Decluttering the Pandemic: Marie Kondo, Minimalism, and the “Joy” of Waste. Cultural Studies, Critical Methodologies, 22(1), 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/15327086211049703

Thoreau, H. D. (1854). Walden. Boston: Ticknor and Fields.